Editorial

In the first half of the twentieth century, the analysis of the effects produced on the paths of arts and visual culture by the technical reproduction of images in printed media —such as books, newspapers, and magazines— occupied a significant place in critical thinking. A new impulse to this issue was given in the 1960s and 1970s when photography became present in different artistic practices and gained increasing institutional recognition as a particular means of art production. In that context, in opposition to those who assumed that the photographic image fully satisfied the possibilities of its reception process by circulating in any discursive space, writer and critic Susan Sontag (1933-2004) said:

(…) although no photograph is an original in the sense that a painting always is, there is a large qualitative difference between what could be called originals—prints made from the original negative at the time (that is, at the same moment in the technological evolution of photography) that the picture was taken—and subsequent generations of the same photograph. (What most people know of the famous photographs—in books, newspapers, magazines, and so forth—are photographs of photographs; the originals, which one is likely to see only in a museum or a gallery, offer visual pleasures which are not reproducible.) 1

The expansion of digital culture at the beginning of the present century challenged with new arguments the idea of the photographic work as a presence. To some, the physical existence of photography was a question relegated to the pre-digital era since it implicitly carried —according to them— an outdated overvaluation of photography as an object.

Now, after more than a year of online cultural consumption, given the sanitary control conditions imposed by the COVID19 epidemic, the art spaces demand once again our attendance. In them, exhibitions of photographs await us. They offer, in their multiplication, a thousand and one different ways—in techniques, sizes, and frames— of showing photography. Spatial installations have been designed to intensify the discursive potentialities of images and create a particular room atmosphere for visitors. These exhibitions provide us those pleasures and emotions that only can give a close, direct, immediate relationship with art.

By: José Antonio Navarrete

1

Susan Sontag. “Photographic Evangels.” In: On Photography. New York: RosettaBooks LLC, 2005, p. 109

(…) Nothing compared

to the Polaroid experience.

It was a little magic act each

time—nothing more, nothing less. I don’t think I’m romanticizing when I allege that Polaroids were the last outburst of a time when we had certainty, not only in images. We had nothing but confidence in things, period.

Win Wenders

1

Extracted from: Wim Wenders. Instant Stories. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd., 2017. Taken from: The Photographers Gallery Blog, London, October 19, 2017.

thesandpitdotorg1.wordpress.com/2017/10/19/a-true-thing-wim-wenders-on-the-polaroid/

Interview with Adler Guerrier

By José Antonio Navarrete

Adler Guerrier, Self-portrait, 2021

Adler Guerrier, a Haitian born (1975) and Miami-based artist, earned his BFA from the New World School of the Arts-University of Florida in 2000. Among his most important solo recent exhibitions are Adler Guerrier: Wander and Errancies, Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, Saint Augustine, FLA, in 2020, and Adler Guerrier: Conditions and Forms for blck Longevity, California African American Museum, Los Angeles, CA, in 2018. He has participated in group exhibitions in a large number of American art institutions such as Studio Museum in Harlem, NY; Santa Monica Museum of Art, CA; Whitney Museum of American Art, NY; and The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA. His work is part of public collections at Studio Museum in Harlem, Perez Art Museum Miami, and Institute of Contemporary Art Miami. Guerrier is also involved in curatorial practice.

José Antonio Navarrete

You presented a personal exhibition at Pérez Art Museum Miami in 2014 titled Formulating a Plot. Is your current art production connected with the works you included there?

Adler Guerrier

Formulating a Plot was a survey exhibition that began with some foundational works of my practice and included new works done for the show. The exhibition encapsulated the practice and presented various interwoven subjects and themes, grouped in bodies of works. Currently, I work on the notions of landscape, place, history, and architecture in relation to the lived environment. In particular, I focus on the setting in which people are and tell stories of their lives or formulate plots in connection to their realities and ambitions. Formulating a Plot presented photographs from a series developed around the flaneur, also a series of photographic works depicting my domestic space, and in particular my yard, and also, works done in historically black Miami neighborhoods—Coconut Grove, Overtown, Liberty City, and Little Haiti.

In my work, I employ framing and phrasing as strategies to image-making, where images are made within or against the grain of a contextual field. The components of my subject—landscape, place, natural environment, urban environment—are all interconnected in their relations to presence—the photographer and other beings—or an embodiment of a moment or a place. The majority of my work is done here in Miami, where these notions are expressed in light of the city’s history and its relations to the Caribbean and the world, and partly because we are in the tropics where light, water, and perennial verdant layer of leaves, fronds, and

grass are ever present. These conditions shape and color the narratives we tell and guide our outlook on the landscape—like how history may be crowded by the present here. The work tries to recognize the footprint

of certain things, like the natural environment always co-existing with the urban environment. The urban environment harshly pushes away the natural environment, to make a case for itself, its materiality and culture, and its hardened setting for new human-centric narratives to develop.

But thinking from the standpoint of ecology, or a larger anthropological view of the world, the natural environment is always there even if we live inside the concrete and pretend that it is not there.

In my most recent works, I try to lessen the strong differences between urban and natural settings, because they can be seen as regulated or managed spaces, on which are imposed rules, limits, or cultural practices and are found to be historically and intrinsically layered. I make images nestled in these aspects of place. My subject is not nature, but the natural environment, where nature is reemerging or is cultivated, like in a garden. I’m interested in these sites where the natural is bounded. And

in this context we encounter expressions of the natural that work similarly to that of the vastness of nature, in that it replenishes us. That is a sort of distinction that I did not have early in my practice, where a focus on architecture and urban landscape were mostly read through from conditioned social and cultural positions.

JAN

How did photography become your favorite art medium, and why?

AG

It’s not my favorite art medium. I am not sure what it is. But photography plays a significant part in my practice because I’m interested in making images to represent aspects of the real world and photography allows for that. I don’t favor documentary practices, as I find film

and its modes of production—with allowance for speculative narrative

and atemporality—and the notion of the possible within image all

useful. Photography concedes for not just the presentation of the world,

as in documentary evidence of its being, but also its representation, through the formation of images that can be read metaphorically—the camera frames, but the photographer phrases. That is my relationship

with photography.

I have found much inspiration in films, poetry, and literature, where sequences of images, words, or thoughts generate subjectivity, points of views, and discursive positions in a work.

JAN

The third question is not strictly related to the precedent ones. You have been involved in curatorial practice and promoting contemporary art by creating several exhibitions. As an artist, how do you consider your conceptual—or thinking—relationship with other artists in the curatorial process?

AG

In my curatorial projects, I tend to present works around ideas to my liking. More often than not, I have organized exhibitions following familiar lines of inquiry, and where I have found affinities in other contemporary art practices. Artists work in many exciting ways, and their works tend to signal their particular approach to a subject. Curatorial projects grant other forms of reading of art, study, thinking through artworks, and exhibition making as a form.

Water and Memory

Mari Carmen Orizondo’s Photograph

By Félix Suazo

Mari Carmen Orizondo conceives photography as a narrative resource that allows her to tell stories where fiction and document overlap. Born in Cuba and based in the Dominican Republic, her images have to do with events that shaped her family and own life. In Orizondo’s work, the presence of water functions as a vehicle for sensations associated with migration and its protagonists. However, the way she articulates the discourse propitiates us to imagine the living circumstances of anyone who, for whatever reason, must leave his place of origin and undergo uncertainties and losses. Thus, the personal becomes a shared experience.

In Traverse, her solo exhibition in ArtMedia Gallery, Orizondo takes old memories of her aunt as a starting point. The latter was forced to emigrate irregularly from Cuba, arriving in the United States in 1963. A photo of her arrival moment on the shores of Florida and a box with her attire (a dress, shoes, a purse, buttons, a jar of earth, etc.) are the remains of that episode. With photographs she took of those elements, Orizondo constructs a story about what could have been that odyssey between the water and the sky in search of a new horizon.

The project is accompanied by a selection of marine photographs, taken at different hours, that serve as time markers along the journey. The story of the artist’s aunt could be the story of any migrant who confronts the danger of an uncertain route as a liberating option. The exhibition, curated by José Antonio Navarrete, is more than the sum of the records that compose it, resulting in an installation device where photography and space configure the viewer’s journey through Orizondo’s proposal.

Between two temporalities —on one side, the fluctuating tide; on the other, the fixed coast— an interval of anxiety and longing is created, a becoming anchored in the body’s fragility and the strength of desire. Water, genesis, and destiny of life is the linking point, the impermanent element where the memory of all shipwrecks is agitated.

Memories

1842

American photographer Edward Anthony (1819-1888) opens in New York his first daguerreotype gallery at 11 Park Row.

1856

French photographer Félix Jacques-Antoine Moulin (1802-1879) travels to Algeria, colonized by France since 1830, where he stays until the following year and photographs landscapes, urban views, architectures, types, customs, and personalities.

1876

Portuguese-born José Christiano de Freitas Henriques Junior, mostly known as Christiano Junior (1832-1902), who has been settled in Buenos Aires ca. 1867, publishes at his expense the first of two photographic albums titled Vistas y costumbres de la República Argentina. Provincia - Buenos Aires.

1892

On November 25, a group of twenty men founds the Wellington Camera Club in New Zealand, with the objective “to encourage the study and practice of artistic and scientific photography.”

1906

Arnold Genthe (1869, Berlin - 1942, New York), a photographer who operated a portrait studio on Sutton Street, San Francisco, captures the sequels of the earthquake that rocks the city on April 18.

1922

On March 9, the Academia de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, opens a group exhibition of Californian artists, installed by Tina Modotti (1996-1942), with the participation of painters Mahlon Blaine (1894-1969) and J. W. Horwitz, and photographers Jane Reece (1868-1961), Edward Weston (1886-1958), Margrethe Mather (1886-1952), Arnold Schröder (1881-?) and Walter Frederick Seely (1886-1959).

1932

Modern Japanese photographer and designer Shuzo Nakagawa publishes New Compositions in Human Beauty (Jintaibi no shin k?sei), including 12 unbound sheets with one printed photograph accompanied by a text on each one of them.

1939

On June 10, two photographic exhibitions inaugurate in Montevideo, Uruguay, the II Salón Nacional “Cien Fotografías” and the Primer Salón Internacional Sudamericano de Fotografía Artística, the latter to be considered the first attempt to group Latin American photography as a collective cultural and artistic proposal.

1948

The most renowned African portraitist, Seydou Keïta (1921-2001), opens his portrait studio in Bamako, Mali, an early successful business that operates until 1963, shortly after Keita is made

official photographer of the government in 1962.

1955

In Miami Beach, Robert Frank (1924-2019) takes a photograph in the Sherry Frontenac Hotel elevator, which he later includes in his book The Americans, published in France in 1958 and the United States in 1959.

1965

In North Vier-Nam, Lam Tan Tai (1935-2001) and Dinh Dang Dinh (1920-2013) found the Vietnamese Artistic Photographers Association (VAPA), a government sponsoring organization in charge of using photography art practice to support the official communist ideology.

1972

With a preface by Edmundo Desnoes (1930) and design by Umberto Peña (1937), the Siglo XXI Editorial, from Mexico, publishes Para verte mejor, América Latina, a photo-book with images by Paolo Gasparini (1934) that has significant repercussion in the development of documentary photography in Latin America

during the 1970s.

1982

Photographers Paul Weinberg (b. 1956), Lesley Lawson (1952), Biddy Partridge (1950), Peter McKenzie (1955-2017), Omar Badsha (1945), and others co-found Afrapix, a progressive, multiracial photographic group and agency involved in South Africa’s political and educational activism.

2009

Tate organization appoints Simon Baker as its first curator of photography, in charge of the acquisition and research of works for the Tate Collection and contribution to the photography exhibition program at Tate Britain and Tate Modern, in London.

2018

Time Magazine selects photojournalist, teacher, and social activist Shahidul Alam (1955) as a person of the year after being arrested and released from prison because of his public critics of the Bangladeshi government’s violent response to the road safety protest.

Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin

Entrance to the Casbah of Algiers

From the album:

Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin

L’Algérie photographiée. Province d’Alger

1856-1857

News

1 Between Islands and Peninsulas

Installation by Amanda Linares

Bakehouse Art Complex, Miami

November 21, 2020-May 30, 2021

The exhibition proposes a cartography of memory based on a trip made by Amanda Linares between Havana and Miami in 2013. It includes photographic images, books, poetic texts and dissimilar objects that unfold in space.

2 In The Studio

Photographs by Pedro Wazzan

Bakehouse Art Complex, Miami

November 21, 2020-December 30, 2021

The series gathers portraits of artists in their studios taken by Venezuelan photographer Pedro Wazzan in 2020. It is characterized by the meticulous lighting and the handling of saturated color atmospheres.

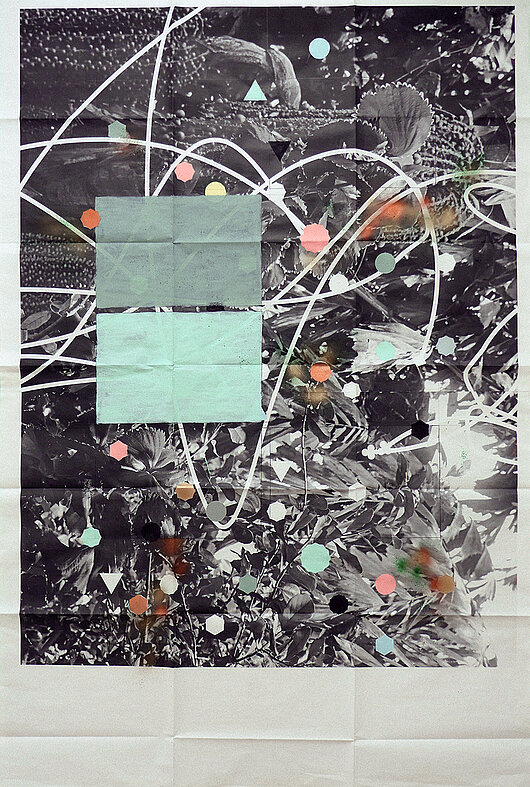

3 Diverse Networks

Oolite Arts

April 21-July 4, 2021

Curated by Laura Marsh

“Diverse Networks” is a group exhibition that explores contemporary mail art collaborations between Miami artists and their foreign colleagues. Among the resources applied, there are photographies, intervened images, objects, and collages. The exhibition provides a documentary link to diverse mail art experiences as a form of reflection and engagement: “From the Fluxus of the 1960s and 1970s to the Miami Dade Public Library’s ArtMobile in the 1980s, mail art is rooted in arts advocacy and radical thinking.”

4 Shared Spaces

Photographs by Andy Sweet

IPC Art Space

May 28-July 31, 2021

IPC ArtSpace presents photographs taken by Andy Sweet that are part of his Miami Beach Project, developed by the artist along with his fellow photographer Gary Monroe from 1977 to 1981. The images exhibited depict the coexistence of Blacks and Jews in Miami Beach. “Sweet’s camera captured what they had in common, their humanity, experiences and social spaces.”