Editorial

It is still difficult to deal with photography as an object of collection, research, and exhibition programs at museums and art centers. It happens even though photography entered these types of institutions more than a century ago and progressively has gained a place within them, albeit with reservations and discrimination.

Most of the analyses on this problem have been centered on the criticism of the conservatism that has fed the distrust towards the artistry of photography. There is no doubt that this is a fertile path for analysis. Nor that the long history of painting and its high early legitimacy still keep it at the core of the artistic field esteem, regardless of how much other art production practices and means have challenged it. However, the distrust of the possibility of preserving photographic images is no less important in this situation. We already know that paintings can be preserved under certain conditions of care for long centuries, but how long a photograph —always seemingly threatened to fade away— can last? This questioning is fueled by the fact that photography is subjected to permanent changes in image-making and printing techniques due to being a technological medium, raising the uncertainty about the durability of its products.

It is stimulating in this respect to corroborate that today, one hundred and eighty years after the appearance of photography, many of the first daguerreotypes have survived. They were precisely those that got access to institutional collections earlier, where they have been subjected to special care both in their handling and in controlling the physical-environmental conditions of their storage and eventual public exhibition. In addition, the scientific practice of conservation has advanced significantly until today, promoting the development of appropriate materials and technological resources for protecting photographic images. The problems of durability, likewise, are now part of the issues considered in developing materials for printing them, such as papers and inks, i.e., of their specific material production process.

Under the current circumstances, the life projection of a photograph can be several hundred years if the proper requirements for printing and aftercare are followed. This projection can be multiplied much more with the progressive advancement of conservation science.

By: José Antonio Navarrete

(…) in 2009 I started to work with a high-resolution digital camera. Suddenly I found myself with an instrument in my hand that was as powerful as a large-format camera. It took me three years to learn how to speak with this new language. By 2012, the whole world had become high-definition. Being able to zoom in on a huge print, and still see detail after detail, is how the world feels now, through my eyes. I’m grateful that I was able to make that development from film to high-resolution digital photography, because it opened up a new language in the history of art. One of the pictures, included in the Hong Kong exhibition, showing the texture of wood and an onion [Sections (2017)], is of such shocking clarity that you find yourself facing an idea of infinity. These pictures contain more information than you can ever remember. Only these large-format prints are able to display the full range of detail, color, and scale, and so digital has actually made the objects almost more unique. The object can only be experienced in the full depth of its presence and its material reality in that room at that time.

“Wolfgang Tillmans: On the Limits of Seeing in a High-Definition World.” (Excerpt from an interview by Aimee Lin.) World Magazine, MoMA, January 11, 2022.

Interview with Adriana Herrera and Willy Castellanos, Aluna Curatorial Collective

By Félix Suazo

Adriana Herrera and Willy Castellanos. Photo: Alberto Ovalle, 2017

Adriana Herrera is an independent writer, curator, and academic. Willy Castellanos is an art historian, curator, and photographer. Both are part of the Aluna Curatorial Collective, the curatorial instance of the Aluna Art Foundation, created in 2011 in Florida to resituate Latin American art in the United States in non-hegemonic dialogue with the international scene. They have focused on building bridges with different thought spaces and other art scenes as a curatorial collective. In this interview, they reveal significant details about photography, archives, and the generation of alternative narratives in their curatorial practice.

Félix Suazo

How has the experience of working together as a curatorial collective been? How do you do when you disagree?

Aluna Curatorial Collective

Meeting each other has made us better curators: our visions complement and enhance each other’s work. Paraphrasing Borges, we can say that our conversations “are happiness,” they give us the joy of materializing ideas by building meaningful dialogues, and we learned that it doesn’t matter “which side of the table” each project comes from.

FS

What importance do you give to artistic photography in the contemporary art scene?

ACC

When we opened the first branch of Aluna Art Foundation in

2011—today nomadic— we created “Focus Locus,” a room for photographic projects. The questioning of the archive is constant in our work. As Foucault understood, that system of statements about the past is usually assembled from power and collectively assimilated. And photography, by its self-nature and closeness to the archive, is the ideal medium to question it and one of the most suitable to develop a series of artistic practices capable of generating new narratives and alternative archives. Many of our curatorial projects approach history as a narrative under construction, considering that the past is always open. We can destabilize its perceptions by using images that often and with increasing recurrence are photographic.

In some cases, this destabilizing potential is found in direct documentary works. In others, it stems from a diversity of procedures

of intervention of the photographic. Both artistic possibilities can expand the scope and nature of the medium and create ways of infiltrating the archive of memory and, therefore, of seeing the present and re-imagining the real.

FS

What aesthetic and conceptual criteria do you consider relevant when working with artistic photography?

ACC

We have been interested in works that, in the convergence of

the personal and the collective, contain the potential to expand the modes of social imagination. We privilege the creative connection between art and life that, going beyond the mere role of what Rosalind Krauss called “an index of reality,” involves practices that can con-move, move a perception or unveil other modes of social understanding and re-elaboration of memory.

We have conceived exhibitions where the archive is constructed by activating the public’s participation, incorporating homemade photographs gathered from calls for entries. In these cases, the notion of authorship dissolves, and the exhibition material becomes a great collective collage. We exhibit non-artistic images, incorporating them into artistic projects, as they constitute insertions in the archival system.

We have worked on recovering and reconstructing artists’ archives from a curatorial perspective in dialogue with history. We inaugurated the only retrospective in Miami of Rogelio López Marín, pioneer of several series that resorted to text and collage to create images of poetic and political resistance, introducing the fictitious into the documentary. Aluna recovered and revalued two decades of Viviana Zargón’s documentary archive on the progressive disappearance of industries in Buenos Aires. Ten years ago, we inaugurated the first retrospective of Cuban Raúl Cañibano in the United States, who managed to create a new imaginary of the island by distancing himself from the narratives

of official photography. We have also addressed the discursive practices of women photographers about their bodies in various projects, as in the cases of Gladys Triana and María Martínez-Cañas.

We are interested in photography when it becomes an active part of a multidisciplinary and experimental exercise capable of expanding social imaginaries. They are the cases of the urban archeologies in the mail art practices of Juan Raúl Hoyos or the social metaphors that Ronald Morán proposes with his labyrinths and invisible and uprooted stairways. Affiliated with these ideas are Ernesto Oroza’s collages, emerging from records of the “architecture of necessity” in Cuba and reinforcing an alternative typology as a popular aesthetics response that surpasses official regulations.

Displacement as a strategy has also crossed our curatorial practice. In The Object and the Image, we present photographic compositions made from intervened objects, bringing together the representation and its referent in the same space. Aluna managed to exhibit, for the first time, after three decades, the photographic and installation work of the Cuban collective Hexágono. The group fused art from the earth -but bringing it inside the white cube- and conceptual photography. We value every language that takes the risk of questioning established discourses of representation and rethinking our “here and now.”

Magüi Trujillo

The fabric of life

By José Antonio Navarrete

The practice of contemporary art opened to the artist the possibility of working with nature without being constrained in one way or another to the limits of the pictorial genres related to it: landscape and still life. Magüi Trujillo has developed her work seeking to achieve this objective, or more precisely, trying to turn her exploration of nature into a discourse on the self and its spiritual dimension.

That is why, even though her images may often function individually according to the imperatives of “good photography,” her work −at least in her last two projects exhibited at Artmedia Gallery− is better oriented towards creating what could be called complex perceptual situations.

She constructed the discourse by grouping several constellations of photographs, each composed of various images or even a small serial segment of independent pictures. These constellations are constituted as a net where meaning is articulated. Consequently, the whole work acquires its density and potential implications in its spatial installation and the complex interweaving between the constellations that integrate it.

With this strategy, which is the result of a careful process of editing and mixing images, the artist combines, in her proposal Weaving in Silence, visual consistency with a meditative approach to nature. Exploring perceptibly in multiple ways the vegetal formation known as the mangrove, characterized by numerous connections among its constituent elements, Magüi Trujillo proposes nature as the force that models the material world, including humans. And, simultaneously, as a laboratory of spirituality.

Memories

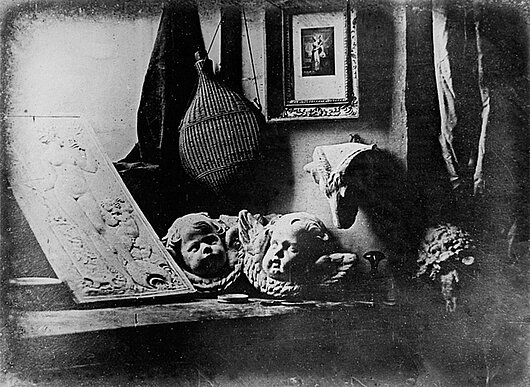

1837

Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851), one of the two inventors behind the daguerreotype, is the author of L’atelier de l’artiste, the oldest known made by him and today remaining in the collection of the Société Française de Photographie.

1855

For his photographs, French painter and photographer Victor Deroche (ca. 1823-1886) won in Chile the Medalla de Tercera Clase at the Exhibición Nacional de Artes e Industrias.

1873

Ten years after arriving in China as a medical doctor with the London Missionary Society, Scottish Dr. John Dudgeon publishes in Beijing, in Chinese, On the Principles and Practice of Photography, a manual oriented to beginners and considered the first of its kind produced in the country.

1902

An advertisement of Fred Hand, Photo Studio, included in the first directory of the Miami Telephone Co., is also the first news about a photography studio in this city, which specializes in “portraits and enlargements” with “all work guaranteed.”

1912

Bangladeshi photographer Golam Kasem, known as Daddy (1894-1998), took up photography as a teenager, buying his first box camera in 1912 and beginning a long career as an active amateur photographer.

1921

Yi Hong-gyeong opens her Buin Photo Studio in Seoul, the first one in the city running for a woman and exclusively dedicated to female customers.

1928

German photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897–1966) publishes his book Die Welt ist schön (The World is Beautiful), a collection of one hundred photographs that exemplifies the modern esthetic of The New Objectivity flourishing in the arts in Germany during the Weimar Republic.

1936

In Buenos Aires, on November 18, a large group of amateur photographers founds the association Foto Club Argentino, which promotes the local photographic art practice and contributes to placing Argentinian photography in the international network of photo-club exhibitions.

1943

At the beginning of his career as a photojournalist and documentary photographer, Indian Sunil Janah (1918-2012) travels to Bengal to cover the damage caused by the famine and makes a body of work that brings him early recognition.

1954

The Photographic Society of Southern Africa, founded on July 26, in Durban, at the Photographic Congress of Southern Africa, declares itself open to all photographers and photographic societies from the country and overseas.

1966

Hellen Johnston (1916-1989) founds the Focus Gallery on Union Street in San Francisco, the first one devoted to photography as fine art on the US West Coast.

1973

South African photographer David Goldblatt (1930-2018) publishes On the Mines, the first of his several books that contributes to shaping the visual understanding of South Africa under the Apartheid regime.

1984-1989

Mexico’s editorial Fondo de Cultura Económica publishes the Colección Río de Luz (River of Light Collection), a photography book series of nineteenth titles each dedicated to one or two artists from Mexico or abroad —mainly Latin America— or a subject.

2012

With its seat in Tel Aviv, PHOTO IS:RAEL is founded as an organization dedicated to promoting the art of photography in Israel and abroad.

2022

On May 14, Christie’s New York auctions, as part of Christie’s Spring Marquee Week, the iconic 1924 Man Ray’s piece Le Violon d’Ingrès, which an anonymous buyer acquired for $12,412,500.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

The Artist’s Studio:

Still Life with Plaster Casts, 1837

Daguerreotype

6.5 x 8.5 in.

Société Française de Photographie, Paris

News

1 María Martínez-Cañas. Absence Revealed

The Bass Museum of Art, Collins Avenue, Miami Beach

April 14 – October 23, 2022

Curated by Leilani Lynch

Photographer María Martinez-Cañas’ Absence Revealed series at The Bass Museum of Art recreates significant events in her personal history through a combination of images and found objects. The works explore the physical and emotional effects of loss and absence, re-establishing the role of family archives and memory. According to the artist herself: “I reflect on the closely related subjects of archive and memory. This often results in an examination of both the human need for conclusive stories and the question of whether anecdotes fictionalize history.”

Martínez-Cañas received a Pollock-Krasner Foundation grant and many awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts grant (1988) and a Civitella Ranieri Foundation fellowship (2014) in Umbertide, Italy. Her photographs are in private and public collections.

2 Marisol and Warhol Take New York

Perez Art Museum Miami-PAMM

April 15 – September 5, 2022

Curated by Jessica Beck

Comprised of numerous works and accompanied by many photographic and video documents, the exhibition Marisol and Warhol Take New York at the Perez Art Museum Miami recreates the simultaneous rise of these two personalities in the New York art scene of the early 1960s. For both of them, the photographic image and video constitute an important creative reference in constructing their particular imaginary and developing their works. The exhibition includes portraits, exhibition records, and captures of intimate facets of the relationship between these two pop art pioneers.

3 Photographing the Fantastic

NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale

On view through October 16, 2022

Curated by Bonnie Clearwater, Chief Curator of the NSU Museum of Art

The Photographing the Fantastic exhibition features a selection of photographs from the NSU Art Museum collection. The works comprise different ways of approaching the subjective imaginary. The space, the body, the memory, and the identity are constant referents that evoke unexpected and enigmatic situations.

Participating artists include Berenice Abbott, Alexandre Arrechea, Wynn Bullock, Edward Burtynsky, Magdalena Campos-Pons, Gregory Crewdson, Anna Gaskell, Ann Hamilton, Mona Hatoum, Kati Horna, Samson Kambalu, Louise Lawler, Nikki S. Lee, David Levinthal, Vera Lutter, Loretta Lux, Ana Mendieta, Abelardo Morell, Zanele Muholi, Andrés Serrano, Onajide Shabaka, Cindy Sherman, Víctor Vázquez, Gillian Wearing, Carrie Mae Weems, and Susanne Winterling.

4 Stereographs of Florida And The Caribbean

HistoryMiami Museum

Online exhibition

historymiami.org/exhibition/stereographs-of-florida-and-the-caribbean/

The HistoryMiami Museum presents an interesting online exhibition entitled Stereographs of Florida and The Caribbean from the institution’s image archive. Stereo views, also known as stereo cards or stereographs, became popular with the general public during the second haft of the XIXth century. Stereography allowed the viewer to look through two lenses focused on a card containing two nearly identical pictures, giving the viewer the illusion of a single image in three dimensions.

The popularity of stereographs coincided with the increasing settlement of Florida. Early stereo views mainly featured the developing tourist meccas of Jacksonville and St. Augustine. Improved transportation routes later facilitated the production of images of Tampa, St. Petersburg, Palm Beach, Miami, and the Everglades. Photographers specialized in depicting panoramic landscapes, bucolic agricultural views, natural wonders, and people working in fields and relaxing at home.