Editorial

While an invisible organism threatens humanity and keeps the world on alert, images that were taken by a robot reach us from the planet Mars. All this happens thanks to the mediation of a technical interface. One brings the distance closer and shows the immeasurable, just at the moment when an invisible virus attacks our bodies. For both the distant and the near, photography is there.

With the help of an electron microscope, biologist Elizabeth Fischer and the team at Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Montana have obtained images of the world’s most dangerous pathogens, including the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, which is 10,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair.

Beyond the power of electron microscopy, 54.6 million km from Earth, the Perseverance Robot transmits information and images of the Martian topography, using an array of devices called Hazard Avoidance Cameras (HazCams), composed of 23 cameras and 3 antennas.

Between these two extremes, the biggest challenge is to appreciate what it is within the range of our sight: the plants in the garden, the cat on the sofa, the woman in the supermarket, the carpet in the bedroom or the masked people protecting themselves from an invisible virus. Those details are what fix our permanence in the world, even if curiosity or the scopic drive (scopophilia) takes us to another planet or to an imperceptible organism.

In About Images # 5 we explore the itinerary of the photographic gaze and its space and time locations. We delve into the role of archives and memory in the interview with Elizabeth Cerejido. In the page dedicated to the artist G.A. Jakubovics, we take a look at his intimate and everyday space. In Ideas, we highlight the voice of Jacques Rancière, one of the most influential authors regarding the discourse of images and their political effects. The images touch inaccessible or little-traveled areas in all these approaches, but what remains important to us is their re-dimensioning as a human event.

By: Félix Suazo

“What is called an image is an element in a system that creates a certain sense of reality, a certain common sense. A 'common sense' is, in the first instance, a community of sensitive data: things whose visibility is supposed to be shareable by all. (…) The point is not to counter-pose reality to its appearances. It is to construct different realities, different forms of common sense—that is to say, different spatiotemporal systems, different communities of words and things, forms and meanings.”

1

Jacques Rancière. “The intolerable image.” In: The emancipated spectator (Translated by Gregory Elliott). London – New York: Verso, 2009, p. 102.

Interview with Elizabeth Cerejido

By Félix Suazo

Photo: Self-portrait, 2021

Elizabeth Cerejido (b.1969) is a curator, art historian, and administrator. She received a BA in Art History from Florida International University (2002) and a MA in Latin American Studies from the University of Miami (2009). She obtained a Ph.D. in Art History from the University of Florida. She currently serves as Esperanza Bravo de Varona Chair of the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami.

She was curator at the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Art at Florida International University from 2002 to 2007 and assistant curator of Latin American and Latino Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, from 2009 to 2011.

She also practices photography as an art and has exhibited her work in the US and abroad.

Félix Suazo

Photography, the document, and the archive are closely related. How does this link manifest itself in the Cuban Heritage Collection?

Elizabeth Cerejido

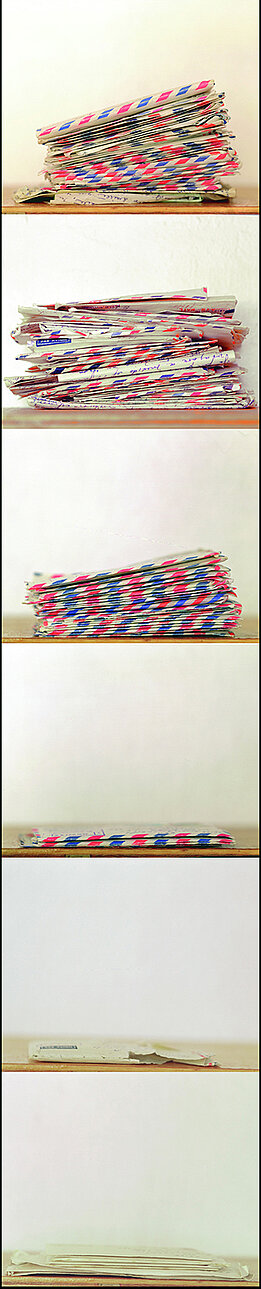

In the context of the Collection, photographs are one of various types of material that comprise our archival holdings; like correspondence, papers, audio visual, born digital and digital materials and other ephemera, their primary function in the archive is to support research, which is our core mission. In the case of the CHC, our photography collections date from the mid-19th century to contemporary manifestations of the medium.

It is well established that beyond their research and historical value, photographs also have an aesthetic and artistic import, yet in the context of the “archive” this gives rise to the question about the role of materials considered “Art” within a collection like the CHC. This latter aspect or way of understanding photography within the context of a repository aligns with my own background as museum curator and art historian; I soon found that this approach sometimes differs from the way archivists and librarians see the role of contemporary photography within that space. Questions around reconciling these two visions or roles (art curator vs. librarian), if you will, with regard to the role of photography, was the topic of an early conversation I had with my colleagues at the CHC, which was illuminating for me.

A photograph, I argue, has both medium-specific and content-specific information that can be “read” as any other type of archival document. However, a photograph also has technical characteristics specific to the medium that similarly informs the way it is “read” and thus opens up other avenues of inquiry relative to its research, historical, and artistic values.

FS

How is your research around photography articulated with your own photographic work?

EC

I consider my practice as a photographer to be separate from my interests or engagement with the medium as a researcher or art historian. From my role as a practitioner, photography is a tool for expressing myself as an artist; a space for creative experimentation that is actually quite inward facing and personal. Reconstructing a Family Portrait, Absence, and Dislodged, the titles to some of my more recent series’, were the means through which I addressed and dealt with such intimate issues as my parent’s story of love, separation, and loss, the sudden death of my father, and the gradual but devastating effects of my mother’s dementia from Alzheimers. I recreated personal histories and memories—both of real and imagined events in my life—by combining still images, 8 and 16mm film, and sound; each series was conceived as an installation, a narrative.

FS

As a scholar of Cuban art inside and outside the island, could you comment on the role of artistic photography in this process?

EC

I will begin with the subject of my Master’s thesis, which focused on photography in Cuba from the 1970s. I was curious about what role photography played during a period that was no longer defined by the euphoric images of the triumph of the Revolution that dominated the 1960s. I found that the work of a generation of photographers that emerged during two distinct moments in two major publications—Cuba Internacional in the early 1970s and Revolución y Cultura in the second half of the decade—was imbued with a personal aesthetic vision and that these publications came to symbolize spaces of relative artistic freedom that wittingly, challenged the artistic structures imposed by the cultural politics of the time. From the journalistic work of Iván Cañas and José Figueroa and Ramón Grandal to the work of younger practitioners such as Gory (Rogelio López Marín), José Manuel Fors, to name a few we can see how ultimately, by the late 1970s, photography would influence the art making processes that generated aesthetic ruptures in the 1980s. However, it is not until the 1990s when artists such as Juan Carlos Alom, Marta María Pérez Bravo, and later Carlos Garaicoa, Ernesto Leal and Manuel Piña, that photography would be considered a significant vehicle for artistic expression.

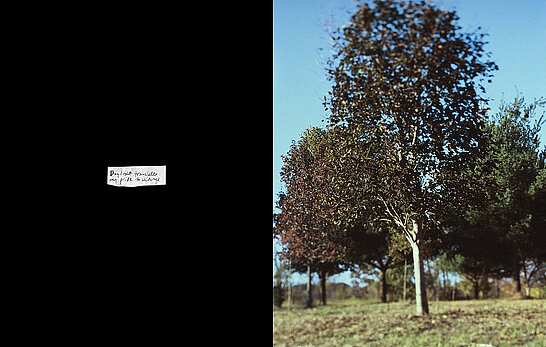

A Place for Affections

G.A. Jakubovics

Diptych 1:

Untitled #1, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2020

Untitled #2, Miami Beach, Miami-Dade, FL, 2019

Diptych 10:

Untitled #19, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2016

Untitled #20, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2021

Diptych 2:

Untitled #3, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2020

Untitled #4, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2020

Diptych 12:

Untitled #23, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2016

Untitled #24, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2021

Diptych 5:

Untitled #9, Aventura, Miami-Dade, FL, 2019

Untitled #19, Wynwood, Miami-Dade, FL, 2020

When the photographer looks around

About G. A. Jakubovics right now

By José Antonio Navarrete

Until now, G.A. Jakubovics has kept the focus of his photographic exploration on the meaning of place. His search, however, has been far from the immediate definitions that the dictionary gives about this word. Early, he was interested in looking for Miami's possible cultural code. He photographed the city intensively to finally find that it is integrated not for one but by an accumulation of them: all different, with distinct origins, and coexisting in a particular urban and cultural profile. For me, that was the essential paradoxical vision Jakubovics proposed in his series Seeking a Code. Photographs of Miami exhibited at Artmedia Gallery in 2017. Being a newcomer, he avoided taking distance from the unknown city and involved himself in its traits.

While Jakubovic was running throughout Miami seeking a code, he realized that the city could be for him not only a place for living but for creating his universe of fondness: for life, people, friends, family, places, nature, and anything else. Then, he started to work on this path. The current Jakubovics exhibition, A Place for Affections, presents a new group of photographs. In them, the authorship accent is put on intimacy, home, and the familiar places that already are part of the photographer's itineraries, even as spots of his quotidian gaze when he looks around.

These two repertories of works have a long and resistant thread that links them independently to their different city approach. They seem to be part of a process of understanding and belonging. They refer to the principal moments of this process. In this case, if the means of comprehension imply an inquiring look, the creation of belonging demands emotional interchanges. A Place for Affections is like a collection of small gestures. Photography can be a warming hand.

Memories

1843

The earliest information about photography practice in Argentina appears in August, in several newspapers, when the New Yorker John Elliot advertises his new daguerreotype studio in Buenos Aires.

1854

On January 14, the world’s longest-running magazine on photography, The British Journal of Photography —initially The Liverpool Photographic Journal— publishes its first issue.

1864

Prussian-born John Edward Saché (1824-1882), former Johann Edvart Zachert, emigrates from the US to Calcutta, in British India, where soon he founds Saché & Westfield, a photographic studio, in partnership with W. F. Westfield.

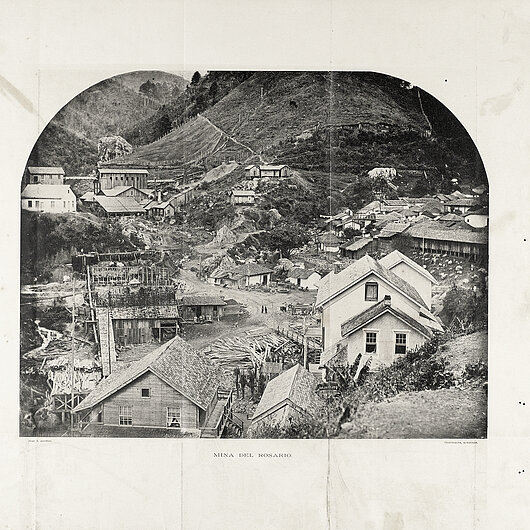

1889

Cuban photographer Juan T. Aguirre, settled in Tegucigalpa, capital of Honduras, illustrated the Antonio Vallejo’s book Primer Anuario Estadístico: Correspondiente al año de 1889, printed by Tipografía Nacional.

1904

Photographs by Alice Seely Harris (1870-1970), a British missionary and photographer that documented the atrocities against the population in the colony Congo Free State, are published in King Leopold II’s Rule in Africa, a book written by her country fellow journalist and politician Edmund D. Morel (1873-1924).

1920

Martín Chambi (1891-1973) settles in Cusco, where he opens a professional photographic studio that brings him extensive fame.

1930

Iwata Nakayama (1895-1949), Hanaya Kanbei (1903-1991), and other local amateur photographers from the Ashiya area near Kobe, Japan, found The Ashiya Camera Club (ACC), an organization known to gather some of the most influential modernist photographers in the country.

1940

With his husband, George Farkas (Budapest, 1905-Miami, 1961), an architect, interior designer, and industrial designer, Klara or Clara (Budapest, 1910-Miami, 2014) settles in Miami, where she soon starts to practicing photography in genres such as portrait, architecture, and advertising.

1947

After a previous partnership with his brother Angelo running a photo-studio in Cairo, Egypt, between 1941-1947, Turkish-born photographer Van Leo (1921-2002) opens his own in the same city, which quickly transforms into the center of a glamorous photographic style inspired by Hollywood.

1953

A pioneering figure in Ghanaian photography, James Barnor (b. 1929) opens Ever Young, his first portrait photography studio, in Jamestown, a district of Accra, but at the same time contributes to print press as a freelance photojournalist.

1970

The exhibitions Galería de Arte, by Emilio Hernández Saavedra (1941), and Introduction to Cinematography, by filmmaker Mario Acha (1941) with the collaboration of photographer Fernando La Rosa (1943-2017), both inaugurated in Lima, Perú, give an account of the new uses of photography as a tool for documentation and analysis in Peruvian art practices.

1980

From March 18 to 29, at the non-profit art space The Kitchen, located at 59 Wooster Street, later acclaimed conceptual photographer Cindy Sherman (b. 1954) presents her first solo exhibition in New York, Untitled Film Stills, based on her recent series with the same title.

1997

In Beirut, Lebanon, the non-profit Arab Image Foundation (AIF) is established to collect, preserve, and research photographs from the Middle East, North Africa, and the Arab diaspora in the lapse between the beginnings of the medium and the present.

2004

Under the Culture Ministry’s tutelage, in Bamako, Mali, the Government founds the Maison Africaine de la Photographie, a public institution devoted to collect, conserve, and promote Malian and African photography.

2020

On Saturday, December 6, one day after its failed planned opening, the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), a five-story building located in the heart of Bengaluru, a city in Southern India, launches digitally and postpones its facility inauguration to 2021 due to COVID19

Juan T. Aguirre

Panoramic view of the mining

camp at El Rosario mine,

San Juancito, Honduras, 1889

News

1 Edward Steichen: In Exaltation of Flowers

Boca Raton Museum of Art

Mar 24, 2020-Jan 3, 2021

The exhibition’s core is seven monumental panels, with floral allegories, painted by Edward Steichen (1879-1973) between 1911 and 1914 for Eugene Meyer and his wife Agnes’s Park Avenue home. From the Boca Raton Museum of Art collection, Steichen’s and his collaborator Alfred Stieglitz’s photographs are displayed in front of the panels, including a 1903 photogravure portrait of Auguste Rodin in his Paris studio and a 1936 Florida Jungle landscape on gelatin silver print.

2 Claudia Andújar

ICA Miami

Curated by Stephanie Seidel

Jan 20-May 2, 2021

The exhibition gathers a selection of photographs by Claudia Andújar (b. 1931) taken between 1972 and 1976 in northern Brazil’s Yanomami community. The artist worked with infrared film, colored filters, and the application of petrolatum on the lens to generate light and color distortions.

3 Lyle Aston Harris. Ektachrome Archive

ICA Miami

Curated by Gean Moreno

Sep 23, 2020-May 31, 2021

This documentary exhibition includes 36 photographs and 15 diaries, dated between the late 1980s and early 1990s. It contains images, personal notes by Lyle Aston Harris (1965), and documents related to the African American art movement, academic figures, and political changes in gestation on gender, race, and inclusion during that period in New York.

3 The Body Electric

Museum of Art and Design at MDC

Curator: Pavel Py?, Curator, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center

Organized by Rina Carvajal, Executive Director and Chief Curator, MOAD, with Isabela Villanueva, Consulting Assistant Curator.

Nov 5, 2020 - May 30, 2021

With more than 50 artists, the exhibition focuses on the relationships between the real, the virtual, the body, and the machine exploring identity, sexuality, and power through a large group of works. Among the different art media and supports, photography satisfies two distinct roles: being the record of performative situations or a specific artwork. The self-portraits of Ana Mendieta, the “autocopies” of Claudio Perna, the stagings of Cindy Sherman, the series of Lorna Simpson posing in the style of black women in the fifties have a significant presence in this context. It is also notable the exhibit of the hologram studies of Bruce Nauman, the selfies of Aneta Grzeszykowska, the queer images of Lyle Aston Harris, the selfies of K8 Hardy, and the fragmented self-portraits of Paul Mpagi Sepuya.